[Last year, Musings paid homage to Produced and Abandoned: The Best Films You’ve Never Seen, a review anthology from the National Society of Film Critics that championed studio orphans from the ‘70s and ‘80s. In the days before the Internet, young cinephiles like myself relied on reference books and anthologies to lead us to films we might not have discovered otherwise. Released in 1990, Produced and Abandoned was a foundational piece of work, introducing me to such wonders as Cutter’s Way, Lost in America, High Tide, Choose Me, Housekeeping, and Fat City. (You can find the full list of entries here.) Our first round of Produced and Abandoned essays included Angelica Jade Bastién on By the Sea, Mike D’Angelo on The Counselor, Judy Berman on Velvet Goldmine, and Keith Phipps on O.C. and Stiggs. Over the next four weeks, Musings will continue with another round of essays about tarnished gems, in the hope they’ll get a second look. Or, more likely, a first. —Scott Tobias, editor.]

One of the most pivotal moments in Michael Mann’s career came in the year 2000, as he and cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki were location scouting for the director’s long-gestating Muhammad Ali biopic Ali. After shooting digital video (DV) of potential settings at night, as reported in American Cinematographer magazine, both men “began to fall in love” with what they saw in their test footage. “I was stunned by this one quality it had, which was not like moviemaking,” Mann recalled years later, discussing his discovery of DV. “There was a truth-telling style to the visuals, and the emotions were more powerful because it didn’t feel theatrical. I analyzed afterwards what was going on to make me feel this way, and I realized it was because we had subtracted the theatrical lighting… Everybody unconsciously sees it and knows that it’s something crafted, not something that feels real. That subtraction of the theatrical convention of how we light is very powerful.”

From his earliest efforts, Mann had tried to find compelling ways to depict subjective experience—to get behind a character’s eyes and find the emotional context of their actions. And digital photography gave him a tool that at once represented both the freedom and prison of subjectivity. On the one hand, as the director observed, it eliminated some of the artifice that so often mediates what we’re seeing onscreen; the video, especially when shot in low-light and natural conditions, had a jarring immediacy to it. At the same time, however, the pixellation lent everything an abstract quality, as if the images became more unstable the closer they got to reality.

Even as high-definition technology improved and the entire industry started shifting over to all-digital productions, Mann found ways to lean into the electric edge of video, highlighting its more otherworldly qualities—qualities that would come to dominate the filmmaker’s later works. Instead of offering a more fluid, “realistic” experience, each new picture would prove to be even more fragmented, a canvas of competing perspectives, gestures, textures, and tones. This alienated audiences to some degree. Seemingly commercial, star-studded endeavors like Miami Vice (2006) and Public Enemies (2009), while they did have their share of vocal defenders, were relative disappointments at the box office, in part because viewers found the use of video to be awkward, disorienting, ugly.

A similar sense of disappointment greeted Mann’s long-awaited cyber-thriller Blackhat when it was released in January of 2015. If anything, the backlash was even greater. While Miami Vice and Public Enemies had done some modest business, Blackhat proved to be an outright disaster. For Mann’s previous efforts, his studio, Universal, had stood behind him. “The key on looking at the profitability of Michael’s movies is that they’ve got a very long tail, well after the theatrical run,” the company’s then-co-chairman Marc Shmuger said in 2006. “[The films] do fantastically well in video, on all television outlets, overseas.“ But in the case of Blackhat, its expansion into several international territories—including star Chris Hemsworth’s native Australia—was scrapped within a couple of weeks of the domestic release. (Frankly, we’re probably lucky we even got a Blu-ray.) It didn’t fare much better critically. While some high-profile reviewers such as Manohla Dargis and Peter Travers praised the film, most were unimpressed and even annoyed.

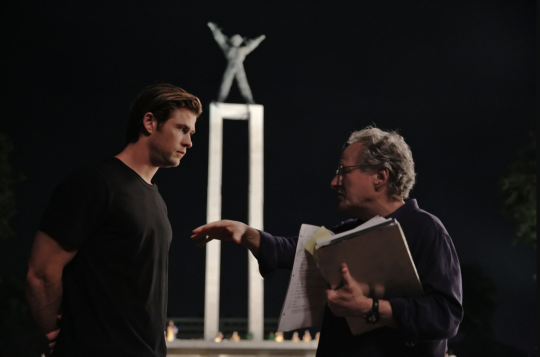

A year after Blackhat’s release, at a Brooklyn Academy of Music retrospective of his work, Mann unveiled a director’s cut that switched the order of certain major narrative developments, and brought a bit more focus to other characters besides Hemsworth’s. While this new version was an improvement, it did also delete certain important scenes from the film. Mann suggested at the time that he was still toying with the movie. Don’t be surprised if yet another cut eventually emerges; even he’s not entirely pleased with the picture, it seems.

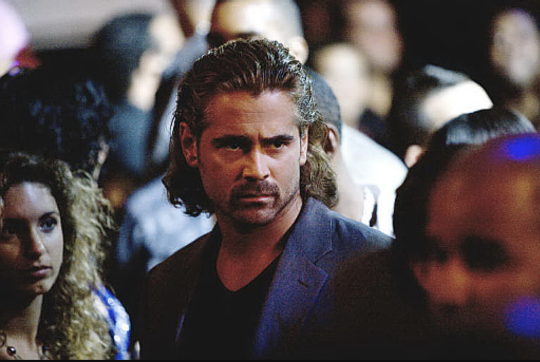

Blackhat follows the efforts of a group of American and Chinese officials as they attempt to track down a mysterious hacker who has attacked a Chinese nuclear reactor and the Chicago Mercantile Exchange. To help them in this endeavor, the government allows convicted hacker Nicholas Hathaway (Hemsworth) to leave prison in exchange for his cooperation. Working together with an FBI agent (Viola Davis) and his old college roommate (Leehom Wang), now a captain in the Chinese army, Hathaway attempts to uncover not only the hacker’s identity, but also his motives and location.

It’s a conventional crime movie set-up with a dose of ripped-from-the-headlines relevance. The run-up to the film’s release focused on the topicality of its premise, which was bolstered by the notorious Sony Pictures hack that resulted in millions of private emails from the movie studio being made public. Eventually determined to be a North Korean cyber-espionage operation designed to punish the studio for releasing the action-comedy The Interview, the Sony hack led to chaos and embarrassment for many in Hollywood and brought home to the rest of us the vulnerability of our online information. All of this seemed to feed interest in Mann’s latest project.

Don’t worry; I’m not about to suggest that Blackhat flopped with audiences and critics simply because it didn’t meet the undue expectations raised by the Sony calamity. In truth, Mann had once again followed his own curious muse and made a film whose formal ambition exceeded its narrative ones. And the results are marvelous—a vision of a digital world where seismic events happen with casual ease, while physical reality constantly plays catch-up, all shot in a style that brings a dreamy, free-floating unease to every exchange.

When video liberated Mann, it also turned him, in some ways, into a different director, one focused as much on the textural possibilities of cinema as much as its narrative ones. But in other ways, the director did not change: He still sought to explore his characters’ subjective experiences, and he also still remained obsessed with authenticity. The latter factor has often resulted in his de-dramatizing moments that other filmmakers might play for cheap thrills. Mann’s characters, particularly in the later efforts, talk a lot about procedure and protocol, using language that attempts to approximate the way people in these circumstances might behave in real life. One of Blackhat’s biggest plot points involves hacking into a top secret NSA program that allows Hathaway to discover a clandestine server in Jakarta; the scene is surrounded not by a gunfight or a physical stand-off, but a murmured phone call between the FBI agent and the NSA, and a lot of discussions about who should be in the room when the hack occurs. Its initial consequences aren’t gun battles or SWAT teams but more phone calls, with moderately raised voices—bureaucrats talking to other bureaucrats.

In the Director’s Cut of the film, the chaotic effects of the villain’s malicious running-up of soy prices on the Chicago Mercantile Exchange is conveyed through a scene involving a giant cargo ship attempting to dock in the Netherlands. The captain discovers that the spike in soy prices has suddenly increased the value of the ship’s cargo, which means that the vessel—dramatic music, please—no longer carries the appropriate level of insurance required to enter the port. It’s a fascinating scene, but it practically thumbs its nose at the notion of conventional stakes-raising.

There’s very little narrative “release” in Blackhat. Each plot development is effectively a screen, or veil, behind which we find yet another one: An ID card photo leads to security-cam footage, which leads to a tattoo, which leads to a prison database, which leads to a motel visit, which leads to an e-mail, which leads to a Korean restaurant, which leads to more security-cam footage, which leads to a testy messaging exchange, with still no clue in sight as to who the villain is or what he wants to do. Sure, there’s a fight or two along the way, and a body count, but the film’s narrative through-line is one of frustration and obfuscation. Even the bad guy’s ultimate aim is not world domination or revenge—easy motivations to understand—but cornering the market in tin through an almost absurdly circuitous route.

By stringing us along in this manner, and presenting what at times seems like a wild goose chase that spans the whole planet, Mann exposes just how thoroughly technology has infiltrated our lives, and how vulnerable that makes us. There is a slow-burning paranoia throughout Blackhat, amid all these seemingly minor exchanges and hushed-voice conversations. And the director makes sure to include lots of shots of surveillance, both actual and symbolic: When our heroes visit Hong Kong, a giant billboard with a face on it hovers in the street outside their rooms, adding to the unnerving sense that they’re all being watched.

In some ways, Miami Vice, Public Enemies, and Blackhat could be seen as a trilogy: Although they are all ostensibly crime dramas, they’re ultimately the work of someone obsessed with technology. Miami Vice, filled with screens, depicts the fluidity of identity in the modern (or should that be post-modern?) world: Its heroes are constantly pretending to be someone else, and with each new persona they seem to lose sense of who they really are. Public Enemies is all about an old world being taken over by the emerging modern surveillance state. As the old-school bank-robber John Dillinger (Johnny Depp) is pushed away by the newly-technologically-emboldened mob and cornered by a newly-connected federal policing bureau, the very texture of the film changes, and the movie-like images onscreen give way to highly-pixelated, low-light video. It’s a formal analog to the story’s central conceit.

In Blackhat, law enforcement and the criminal element are no longer extending their individual networks; they’ve essentially merged, so that one can enter the other with the click of a button. While the film is filled with plenty of the kinds of quiet, brooding close-ups of which Mann is so fond, it’s also a movie of wide shots and patterns, of grids both real and imagined. Its visual scope is impossibly broad: The camera dives deep into the circuitry of our digital age, but it also pulls back to reveal the blinking, endless lights of our 21st century cities, drawing an explicit connection between the nano-imagery of the cyber realm and the macro-imagery of the cityscape. The film opens with a depiction of a malicious computer worm entering a network, but the process is presented not as text on a screen but as a surge of lights taking over a dense field of blocks, almost like an invading army of luminescence entering a darkened city. Over and over again, the camera finds images that resemble a motherboard or microchip—a trellised bridge here, a patterned balcony there. One major shootout takes place against a series of ominous structures that look like the surface of an integrated circuit board.

Hathaway may be fluent with technology, but at first he’s a character who is imprisoned in his own mind, who doesn’t fit the patterns of the world around him. Nevertheless, he has to navigate this milieu, not just manipulating the digital landscape around him but also physically trying to locate his quarry: the rogue hacker Sadak (Yorick van Wageningen), wreaking havoc on the planet’s markets and nuclear reactors. As such, the film depicts a process whereby Hathaway moves away from the grid (both conceptually and visually). In the climactic face-off, set amid a traditional Indonesian ceremony, a crowd of dancers and marchers in colorful garb move in unison, while Hathaway locates and then stalks his prey, in slow-motion, trying to blend into his surroundings. The effect is that of watching a virus insinuate itself into an established pattern, and Mann revels in the cinematic splendor of this idea.

In effect, the whole film charts Hathaway’s attempt to get closer and closer to the rogue hacker—to lift all the digital screens until there is only the physical. “It’s not about ones, or zeros, or codes,” Hathaway yells at Sadak in their final face-off, which is a surprisingly visceral scene—he has to subdue the villain not with computers or guns, but by stabbing him repeatedly in close-quarters combat, using tactics learned in prison. And yet, there’s still something bleak and unfulfilling about this final confrontation. Sadak is silent, maybe even perplexed, as if the reality he’s being presented with were somehow foreign to him. “I’m a gamer,” he says at one point. “I hire others to do sub-symbolic stuff.”

Let’s face it: Only Michael Mann would dare have a villain utter the words “sub-symbolic” during a climactic face-off. But that’s the tension at the heart of Blackhat, between real life, with its bureaucrats and its hushed conversations and obsessions with protocol, and the digital sphere, with its split-second armies of light and its ability to change people’s destinies with casual abandon. The film captures the uneasy cadences and beauty of this new reality, and it possesses an uncontainable truth about the way we live today.