Over the course of their three-decade career, Joel and Ethan Coen have buried a man alive, fed a body into a woodchipper, and shot a grinning Brad Pitt in the face at point-blank range. The most vicious act in their oeuvre, though, involves no physical violence whatsoever. It’s the blunt verdict issued by a famous French piano teacher, Jacques Carcanogues (Adam Alexi-Malle), after hearing a teenage girl’s audition. “Did she make mistakes?” asks the girl’s patron, who considers her a prodigy. “Mistake? No,” Carcanogues replies. “It say E flat, she play E flat. Bing, bing. She play the right note—always.” Nonetheless, he refuses to accept her as a pupil, insisting that her playing, while technically impressive, is emotionally sterile. “The music, monsieur, she come from l'intérieur. From inside. The music, she start here,” he explains, gesturing to his heart. Perhaps she might make a good typist, he suggests. “I cannot teach her to have the soul.”

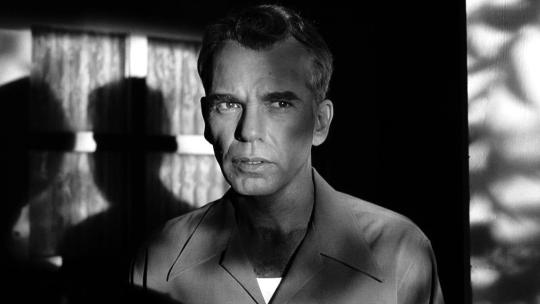

This exchange occurs late in The Man Who Wasn’t There, the Coens’ black-and-white film noir riff about a taciturn barber, Ed Crane (Billy Bob Thornton), whose spontaneous decision to invest in a dry-cleaning business (without having the necessary funds) leads to tragedy. At the time of the film’s release, in 2001, Carcanogues’ words pointedly echoed the most common criticism of the Coen brothers: that their films are superficially clever but fundamentally empty, little more than self-conscious genre riffs. That complaint doesn’t get lodged as frequently these days, in part because Joel and Ethan finally made an overtly personal movie, 2009’s A Serious Man, that reflects their own suburban Jewish upbringing. But The Man Who Wasn’t There remains their most wrenching cri de coeur, even if its heartfelt aspects are deliberately buried deep.

The film’s very first line, spoken by Ed in voiceover narration, insists that appearances don’t tell the whole story: “Yeah, I worked in a barber shop, but I never considered myself a barber.” Ed wants us to look past the surface—which is crucial, because the surface, when it comes to Ed, could hardly be more phlegmatic. Early on, he introduces us to his wife, Doris (Frances McDormand), and casually reveals that she’s having an affair with “Big Dave” Brewster (James Gandolfini), her boss at the department store where she works. Given the movie’s noir trappings, one might assume a crime of passion to be forthcoming…but Ed seems untroubled by the knowledge that Doris is stepping out on him, shrugging it off with the words “It’s a free country.” Nor does Ed and Doris’ marriage appear to be an especially happy one. They barely talk to each other—indeed, Ed barely talks at all, except in voiceover—and the relationship seems grounded in mutual tolerance. When Ed anonymously blackmails Big Dave about the affair, he explains the scheme strictly as an effort to get enough money to go into the dry-cleaning business. Passion doesn’t enter into it at all.

Or so the Jacques Carcanogues of the world would have you believe. But while Ed never comes out and states his feelings for Doris—that’s not his style—The Man Who Wasn’t There functions almost entirely as a stealth declaration of his love for her. It’s a film in which the motor driving every action purrs so softly that it’s barely audible. Stoicism, the Coens argue, isn’t necessarily the same thing as indifference, and things that look shallow (or frivolous, in the case of their work) may intentionally conceal hidden depths.

Clues about Ed’s true feelings for Doris are strewn throughout the movie. We see them playing church bingo together, and Ed explains why he’s there: “I wasn’t crazy about the game, but…I dunno. It made her happy.” He says these words (like all other words) in such a dry, flat, uninflected tone that it’s easy to ignore or dismiss their clear implication, which is that Doris’ happiness is important to him. Later, gazing at Doris while she sleeps, he begins to tell the story of how they met and got married, but is interrupted when the phone rings. He then leaves the house, proceeds to kill someone, returns home to find Doris still sleeping, and launches right back into the story of their courtship, as if nothing had happened. Murder is just a distraction from the essential. “She looked at me as I was a dope,” he says of Doris, thinking back on the marriage proposal, “which I never really minded from her.” The guy couldn’t be more smitten. He’s just smitten in a way that’s diametrically opposed to the swoony version to which we’re accustomed, and by a person whose brusque treatment of him makes her seem, to us, unworthy of such pure adoration.

That’s also the only plausible explanation for The Man Who Wasn’t There’s most peculiar scene: a flashback (presumably) that occurs while Ed is unconscious following a car accident. What’s odd about this memory is how utterly mundane it is. Sitting idly on his front porch, Ed is chatted up by a salesman (Christopher McDonald) pitching the benefits of tar macadam (a.k.a. tarmac) for one’s driveway. Doris arrives home in the middle of the pitch and tells the salesman to get lost. They both go inside, Ed starts to say something, and Doris stops him. That’s it. This brief reverie has no narrative function whatsoever, and doesn’t even seem to directly address any of the psychological elements in play. The Coens clearly put it there for a reason, however, and its apparent irrelevance, paradoxically, positions it as the movie’s secret answer key. (See also Fargo’s seemingly extraneous Mike Yanagita scene, which actually spurs Marge to solve the case.)

The Coens show remarkable, arguably quixotic faith in viewers’ ability to pick up on subtle details and extrapolate an entire mindset from them. At the beginning of the flashback, Ed looks at his watch; the film cuts from his glance to a close-up of the watch face, just to emphasize the point. Why does that matter? We don’t know when this scene occurs, nor do we have any reason to think that the time of day is important. No prior scene instructed Ed to be ready at 3:15pm, or anything like that. He can only be looking at his watch because he’s wondering where Doris is, especially since she pulls up in her car just a couple of minutes later. He’s impatient for her to get home. In the meantime, he’s totally willing to listen to the macadam man’s sales pitch, which Doris treats as the intrusion that it is. Ed would be lost without her, at the mercy of unscrupulous others—which is exactly what happens in the film’s present tense, as the distance inspired by her infidelity leads him to make one disastrous decision after another. Which makes it all the more heartbreaking when, after the salesman leaves, Ed makes what’s almost surely a rare attempt to open up emotionally and gets shut down by an exhausted Doris, who says merely “I’m fine.” There’s potentially an unspoken undercurrent (where was Doris coming from?), but it remains a mystery.

Still, despite the Coens’ prankish and/or self-protective urge to obfuscate—I’m not even addressing the film’s religious subtext, which is largely conveyed through Ed’s fascination with UFOs—they do ultimately state their intentions quite clearly. Ed winds up in the electric chair, albeit for the wrong murder. A prison official shaves one of Ed’s legs in preparation for attaching an electrode to it, swirling the razor through a bucket of water to clear it of whiskers. It’s no accident that this visually echoes an earlier scene in which Ed shaves Doris’ legs while she’s in the bath, an act that the brothers shoot in a way that makes it looks downright reverential (though at the time that moment is more easily perceived as an act of humiliation tied to his profession). And Ed’s final thoughts before his life is extinguished are both eloquent and plain:

“I don’t know where I’m being taken. I don’t know what I’ll find beyond the earth and sky. But I’m not afraid to go. Maybe the things I don’t understand will be clearer there, like when a fog blows away. Maybe Doris will be there. And maybe there I can tell her all those things they don’t have words for here.”

Ed Crane is a deeply closeted romantic, and The Man Who Wasn’t There is the work of two deeply closeted humanists. Lurking beneath the film’s deceptively nostalgic surface—the stark, monochrome photography; the rueful voiceover narration; the period detail; the familiar genre trappings—is an acute, affecting tale of passion that’s not so much repressed as it is carefully hidden, like an irreplaceable treasure. And lurking beneath that is a message that few, at the time, bothered to decode: We care.