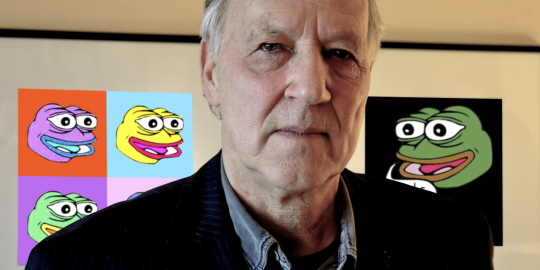

Raffi Asdourian/Flickr (CC BY 2.0) | Pepe courtesy Matt Furie/mattfurie.com | Remix by Jason Reed

Werner Herzog, that hypnotic German filmmaker who once tried to murder his leading man, who taunted death atop a soon-to-erupt volcano, and who looking upon the screeching Amazon mused that he saw only pain and misery in the jungle, was on a press tour. He sat beside his producer Jim McNiel, both bundled up in the Park City cold, and listened politely as the Los Angeles Times’ Steve Zeitchik asked about his new film.

It was 2016 at the Sundance Film Festival, and Herzog’s latest documentary, Lo and Behold, Reveries of the Connected World made its debut in the festival’s Doc Premieres section. The film saw Herzog turning his inimitable lens to the ramifications of modern technology, and initial reviews (at least those counted by Rotten Tomatoes) were uniformly positive. One critic for The Young Folkssaid Herzog took “the same adventurous spirit that made him drag a cruise ship across a Peruvian jungle in Fitzcarraldo” and put it toward exploring “the labyrinth of the internet’s history.” Many more remarked on the film’s wondrous, sobering, and truly Herzogian revelations about man’s place in the midst of an unprecedented technological revolution.

Zeitchik asked Herzog directly, why make a film about the internet?

“We should know in which world we are living,” he responded. “As thinking people, we should try to scrutinize our environment and know in which world we live.”

Well, this is the world in which we live:

Lo and Behold is a commercial.

It was produced by Massachusetts-based network management company NetScout, in conjunction with New York ad agency Pereira & O’Dell; borne not from Herzog’s own passions, but from those of a marketing team seeking to promote a corporation in the midst of a massive rebranding effort. Marketers might bristle at the exact term, “commercial,” preferring instead the term “branded content,” one tool in an industry-wise trend towards nearly-invisible advertising meant to implant a positive perception of a company’s identity.

After Lo and Behold played Sundance, several reviewers mentioned NetScout had provided the funding, but not one writer took that detail further. Critics focused on the film’s structure and Herzog’s larger-than-life persona, and no one stopped to ask just who NetScout was, and why they had made this film. Perhaps it was the promise of Herzog’s integrity and character he had fought and earned for himself throughout his career as cinema’s wild man that kept anyone from asking questions. In what world could the man, who has braved deserts, the antarctic, and war zones in the tireless pursuit of filmmaking, sell out?

Branding Cinema

Historically when one spoke of the cross section of advertising and filmmaking, they spoke of product placement – James Bond drinking Heineken in Skyfall, Tom Cruise wearing Aviators in Top Gun, or E.T.’s beloved Reese’s Pieces. But something different happens when advertising agencies realize that they don’t just have to tag-along on a film, but can influence its very structure.

In the late 1990s, while scripting Cast Away, Tom Hanks and William Broyles Jr. approached FedEx with an unusual offer. They said let us use your company’s likeness, and in exchange you can help produce the film. Hanks and Broyles’ problem was that the inciting event of Cast Away was the gruesomely detailed crash of a plane branded with FedEx’s markings.

Company representatives recalled to The Chicago Tribune:

“[FedEx spokeswoman Sandra] Munoz said FedEx decided that the script highlighting the company’s humble origins, its global reach and can-do spirit outweighed the aircraft disaster. FedEx provided filming locations at its package sorting hubs in Memphis, Los Angeles and Moscow, as well as airplanes, trucks, uniforms and logistical support. A team of FedEx marketers oversaw production through more than two years of filming.”

This new relationship in which a third party’s marketing team oversaw the production of a high-budget film, foretold a major change in the way companies and cinema interact.

A managing director for FedEx said, “As we stepped back and looked at it, we thought, ‘It’s not product placement, we’re a character in this movie.’ […] It’s not just a product on the screen. It transcends product placement.”

In 2001, a year after Cast Away, BMW pioneered their cinematic ad series “The Hire.” The premise was simple: Clive Owen posed through a series of stylish, high-production value action shorts. “The Hire” played at Cannes and was so successful that – in what must be some kind of a first – the Jason Statham hit The Transporter was based on the ads. The genius of “The Hire” is that they are not films about BMW, but films in which the style and power of the automobile act as the architectural underlay for a compelling narrative.

This is branded content. It is not an attempt to insert a brand into a work of art, but to insert a work of art into the brand. As Naomi Klein once described it: ”the goal [of a corporation] is no longer association, but merger with the culture.”

Branded content is a graffiti artist covertly painting original work for a video game company, or a vodka brand working with a music festival to promote gender equality. At its best, it is The Lego Movie, in which the sensory experience of playing with LEGO blocks is lovingly evoked to tell a story. That film’s careful digital animation stands as not just some of the most impeccably textural filmmaking ever attempted, but as a cruise missile of nostalgia aimed at the viewer. The Lego Movienearly doubled the worth of its parent corporation.

Such a thing has never really existed in film before, but it is very similar to the early years of television, when companies like US Steel, Alcoa, or Kraft would pick up the tab for a show in exchange for the prestige of having their name on it. A great deal of powerful programs were produced in this era of television, but none free from compromises. Rod Serling was just one of many talented writers who found themselves increasingly stymied by his sponsors’ patter of seemly changes. In the introduction to the paperback edition of his great teleplay “Patterns,” Serling cautioned us about mixing corporations and art: “I think it is a basic truth that no dramatic art form should be dictated and controlled by men whose training, interest and instincts are cut of entirely different cloth. The fact remains that these gentlemen sell consumer goods, not an art form.”

Censorship eventually drove Serling from writing about contemporary society to The Twilight Zone, where he could explore his stories of intolerance and bigotry in a politically-neutral fantasia.

A NetScout Production

Founded in 1984, NetScout specializes in network systems, producing both hardware and software. It was an early developer of packet sniffers, the technology that logs data being transferred over networks. Today, according to its own online bio, NetScout has a heavy focus on cybersecurity, anti-DDoS and Advanced Threat Solutions tech. It also provides web service performance platforms, cloud management, and packet brokers, among many other interconnected divisions.

All this to say, the company operates behind the scenes. It is not purchasing Super Bowl ad time to become a household name, rather its financial investments lie in the sustained prominence and upkeep of the internet’s infrastructure.

The seed of Lo and Behold formed in 2015, when NetScout was in the midst of a massive company-wide rebrand led by its then-CMO Jim McNiel, who would later participate next to Herzog in the film’s publicity tour. The company had spent the previous year making major corporate acquisitions, including the communications sector of Danaher Corporation, Arbor Networks, Fluke Networks, Tektronix Communications, and VSS Monitoring. The shopping spree consolidated their share of the communications market and helped the company more than double its revenue to the $1.3 billion it generates today. But NetScout remained a largely unheard of entity outside of the inner circle of the network management industry it had helped pioneer in the 1980’s. The company needed a way to boost its status and reach new clients.

And so, Lo and Behold was born in the walls of Pereira & O’Dell’s New York office, where the agency has serviced clients such as Intel, Fifth Third Bank, and Procter & Gamble.

It was Pereira & O’Dell’s executive creative director Dave Arnold who approached McNiel with a fresh, but risky idea. They would make a feature length documentary celebrating the creation of the internet and the boundless potential of its future. It would engage consumers with a focus on the importance of the technological innovations being made today, and toast the creators and engineers who contract with NetScout for their cybersecurity and hardware needs. The kicker: It would be directed by Werner Herzog.

In a 2016 AdWeek reflection on the film, McNiel wrote that Herzog initially balked at the idea, telling NetScout: “No! I do not do commercials.”

But McNiel managed to convince Herzog the film was not a commercial, but a serious documentary that would explore the world-changing and potentially apocalyptic ramifications of the internet.

Speaking to McNiel this month, he told us there was no second choice for a director. If Herzog couldn’t be won over, the entire project would be scrapped. Why?

“He’s an icon,” McNiel said. “And he’s a meme!”

Herzog the Meme

Popular arthouse directors have long been a favorite target for ad firms. This past year, Herzog’s friend and collaborator Errol Morris directed a series of 56 commercials for Wealthsimple, in which celebrities from all walks, including himself, tell anecdotes about handling their own finances. Wes Anderson has made ads for American Express, Darren Aronofsky has been recruited by Yves Saint Laurent, and Ridley Scott has made advertising history time again with his Hovis, Chanel, and Apple ads.

Many renowned directors from Scott to David Fincher to George Romero got their start making commercials. In Japan, Nobuhiko Obayashi was so good at TV spots he was given free reign by Toho to make his psychedelic freakout cult classic House. Even David Lynch, one of the staunchest opponents of product placement in cinema, has made commercials for Playstation, Gucci, and Clearblue Pregnancy Test. When asked during a Q&A if he finds this hypocritical, he answered bluntly: “I do sometimes [direct] commercials to make money.”

For Lynch, if the ads don’t bleed into the art then there is no reason for purists to hold directors’ advertising works against them; after all Inland Empire probably didn’t pay very many bills. Spike Lee has even opened up his own ad agency, and often blurs the line between his core filmography and his ad work, licensing to Nike and performing as his Mars Blackmon character from She’s Gotta Have It, retroactively making his feature debut something akin to after-the-fact branded content.

But Herzog was different. He came from the roiling, unfettered New German Cinema of Syberberg and Fassbinder, where they ranted and bled and snorted endless coke for their art. And even among that crowd, he was different. He came from the fringes, growing up in the mountains of Bavaria and making his first films with a camera he stole from a local university. In the 1970s and ‘80s, while his contemporaries in the movement like Volker Schlöndorff and Wim Wenders went mainstream, he kept his distance. His adventures in storytelling have taken him to every continent on the planet, and he has further cemented his legend with tales of being arrested, threatened at gunpoint, forging documents, and picking locks to forbidden zones all in the pursuit of cinema. Alone, the troubled making of Fitzcarraldo has probably done more than anything else to create the idea of Werner Herzog in the mind of western audiences, that of a madman mystic lost in the jungle chasing truth and art while eschewing formulaic Hollywood methods of filmmaking. His explicit anti-commercialism has made him appear incorruptible to his fans, who still at every chance possible put on impersonations of his signature Black Forest accent.

McNiel is right. In the era of the internet, Herzog has become a meme. Many new fans are coming to his works for the first time through YouTube clips from Les Blank’s documentary Burden of Dreams, about the making of Fitzcarraldo. Herzog’s off-the-cuff speech from the documentary about the Amazon jungle representing “the harmony of overwhelming and collective murder” has been uploaded a half a dozen times with tens to hundreds of thousands of hits on each clip, including one by its DVD distributor The Criterion Collection. Comedian Paul F. Tompkins has made Herzog one of his most memorable celebrity impersonations. His more misanthropic quotes have been turned into “Demotivational Posters” by internet users, and Know Your Meme has a full entry dedicated to exploring his presence as a joke online.

Herzog is aware of the online perception of his public persona, and although he has not exactly embraced it he has said it does not bother him and he is content to let parody Twitter accounts exist. As a result, fans who participate in this meme-ification continue to build his mythology. It is through these parodies that the idea of Herzog as a savant, able to pierce through the veil of civilization to reveal humanity’s dark nature, is allowed to flourish. It flourishes because Herzog is authentic, because he is a lawbreaker, an explorer, a true independent.

There is a phrase for the unquestioning devotion to Herzog’s work: Brand loyalty. It is this brand that NetScout sought to tap into it. The hiring of Herzog was as clear-eyed and purposeful as any good corporate acquisition. His prestige (or “brand equity,” as a corporate board of directors might put it) opened doors that NetScout’s opaque public image kept shut. McNiel confirmed this: “We did not really get any flat-out rejections [from interview subjects]. After all, this was Werner calling.”

Designing “The Connected World”

Since Lo and Behold’s primary purpose was to serve as an innovative business-to-business marketing initiative, it would need to speak to corporate clients by highlighting the world-changing technologies they were pioneering and celebrating the radical social impact their developments have had on the world.

It was McNiel who came up with the film’s 10 chapter structure and the list of interviewees. Prize gets like Bill Gates and Jeff Bezos couldn’t fit Herzog into their schedule, but others like Elon Musk and hacker icon Kevin Mitnick did. According to McNiel, Herzog did conduct his own research and suggested names, and the film came together as a collaboration.

By the end of post-production, McNiel and Herzog had delivered an unique feature that was simultaneously, fascinating, existential, and most importantly a subtle monument of advertising.

But why then did it premiere at the Sundance Film Festival, which still insists it is an independent showcase run by a non-profit?

On social media, branded content is typically flagged with phrases like “Sponsored Content” or “Paid.” But there are no guidelines in place for branded films (indeed no authorities to even issue them). Minor steps are being taken to separate the branded from regular films; Sundance took one such step in 2016 with the debut of their Digital Storytelling showcase specifically for branded content. But that very same year, Lo and Behold played as a traditional documentary instead. Was this another door that the Herzog brand flung open for NetScout?

Each year, thousands of prospective filmmakers, many truly independent, many self-financed and motivated by love of the art and by a desire to have their unique voice amplified, spend $85 for the privilege of having their feature film considered at Sundance – that number goes down to $65 if they’re early and up to a whopping $110 if they’re late. They do the same at Toronto, SXSW, Cannes, Tribeca, Berlin, and the hundreds to thousands of festivals launched nominally in support of independent cinema. Sundance took around 2,000 such submissions last year – likely around $180,000, not including short films. Many filmmakers spend thousands of their own dollars on submissions. There has been remarkably little discussion about the fact that their films will be judged not just against the latest low-budget Hollywood productions indie-laundered through smaller production houses, but now, it seems, also against branded content: the agenda-driven works of telecom giants, car manufacturers, toy empires, and fast food chains.

Advertisers have found a new integrity in iconoclasticism. It is not a long leap from NetScout’s employment of Herzog as a modern-day Rasputin to, say, Wendy’s restaurants’ pugnacious Twitter feed. Each seeks to legitimize their company as an honest and self-aware organism, as idiosyncratic and hip as any of us. They are corporations seeking to become that thing they were asserted to be in the 2012 presidential campaign: People.

For the advertisers, it is simply work. They are upfront about their goals and tactics and trade publications frequently profile the individuals developing these campaigns. Often, there is an earnestness, talent, and true passion in their efforts.

“There does need to be some connection between what it is you’re trying to communicate, because you need to be passionate about it,” McNiel said. “The only way this stuff gets any kind of lift is if it’s regarded as real cinema.”

So branded content seeks to slide itself into our lives undetected, emulating the form and scope of “real” cinema.

However, the unusual thing about branded content is not that companies outside the film industry are attempting to make money off of films. Rather, it is that they are unconcerned with making money. Even mega-franchise films like The Avengers tend to proceed from the inside out — a college of production and distribution companies attempts to live off a product. The work of art drives the revenue, and success or failure as a company is based off the success or failure of the film.

But branded content is more opaque. Its success is judged not so much by how well the film itself does financially (a modest documentary like Lo and Behold fits snugly within NetScout’s significant marketing budget), but by softer concepts like reach and influence. Jim McNiel was candid on this point, telling us that “the primary benefit to NetScout behind the film is the number of impressions and perceptions about NetScout” (In the year following Lo and Behold’s premiere, NetScout’s annual media impressions jumped from an average 1.5 - 2.5 billion to more than 25 billion). Advertising is a medium designed to make you feel a certain way about a company. Couple this knowledge with cinema’s proven track record at affecting the audiences’ biases and assumptions and one need not be zealously anti-corporate to worry about the potential for future branded content to misrepresent and mislead the audience.

The Two Werner Herzogs

In early 1954, at the height of the housing segregation issue, while Brown vs. Board of Education was still being heard in the Supreme Court, the most infamous example of early television censorship occurred. Reginald Rose, the celebrated writer behind 12 Angry Men, debuted his new standalone episode for the television series Westinghouse Studio One. Called “Thunder on Sycamore Street,” the episode was based on the true story of a black family moving into a white neighborhood, and their neighbors’ slow plummet into racial violence. The Westinghouse people loved the script for its passion and realism, but had one small, insignificant change: the black family must be changed to, well, anything else. There was no way they would air a program about white Americans attacking black Americans. It was simply too hot a topic for mid-fifties audiences. So Rose re-wrote the script, and the episode that aired was about mob violence against a white family with an ex-convict father. The moral meat of the teleplay was pulled out entirely, but Westinghouse simply could not risk people thinking of that when they shopped for appliances.

It is difficult to know the extent to which such decorous censorship happened with Lo and Behold. A large chunk of the film is devoted to the negative impact of the internet – most hauntingly in an interview with the family of a teenager, Nikki Catsouras, whose gory death in a car crash became a shock image meme. When Catsouras’ mother confesses that she thinks the internet is the modern-day face of the Antichrist, it seems for a moment that the film has at last found its bite. Such melanges of trauma and focused mania are hallmarks of Herzog’s best work. Those qualities are explored in the lion’s share of his films, from the surreal Bad Lieutenant: Port of Call New Orleans to the tragic The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser to the fire-breathing Klaus Kinski performances of his most famous work, and, most pointedly, to his 1981 documentary God’s Angry Man, in which he studies a particularly fiery televangelist.

But the section with the Catsouras family is all too brief. They tell the bullet-points of their story and are gone, as we rush to the next location. Whether that was Herzog’s choice or not, it is difficult to know, but the thumbnail structure of Lo and Behold is a new and unique problem for the veteran filmmaker.

Jim McNiel told us that “the challenge with working with Werner is kind of keeping him from going too far down into the shadow of darkness.” However, he believed the dark elements were important to show, as too much praise of the future without conflict would make for a flat story. Focusing on the darker elements, he reasoned, would equally highlight the film’s more positive moments, allowing for the intended good vs. evil narrative to take hold.

Still, McNiel reported having to rein Herzog in when he went too dark, and it is perhaps his inability to submerge the film in those depths that leaves Herzog appearing at times more unsure of his subject than any other documentary he’s made, except perhaps for his ten minute short on the middling rock band The Killers, promoting American Express’ 2012 Unstaged concert series. While we have alternate terminology available for Lo and Behold, and for his road safety PSA From One Second to the Next(made for AT&T), we have no earthly idea what to call The Killers: Unstaged except a commercial.

After Lo and Behold premiered, it seems only New Republic’s Will Leitch worried about this new side of Herzog. He wrote: “It’s probably a fair question to ask at this point: Do Werner Herzog’s movies need quite so much Werner Herzog in them? There has been a growing fear among longtime admirers of Herzog’s films, of which I am certainly one, that Herzog the Public Personality has been starting to sneak in around the edges of Herzog the Director, and to ill effect.”

But Leitch’s distinctions between Herzog the Public Personality and Herzog the Director are miscalibrated, in the wake of his more recent, prosaic films like Queen of the Desert and Salt and Fire, which reviewers seemed to grit their teeth and swallow like medicine. The division between the Herzogs is more acute.

Until 2005, every Herzog documentary was self-produced by Werner Herzog Filmproduktion and distributed by various high-end channels like Canal+. This changed with Grizzly Man, his 2005 film about the life and death of Timothy Treadwell. That film was co-produced by Discovery Docs, the documentary arm of the Discovery Channel. Grizzly Man is a true masterpiece, one of his best films, and the presence of the Discovery Channel is a natural fit for the material (not least because their 1999 teledoc made Treadwell famous), but for the first time, Herzog made a documentary on someone else’s dime and under the control of a massive corporation. Further, it elevated Herzog to a new level of fame. No longer was he being interviewed by dry cineaste magazines, but on late night talk shows. And his personality was built for internet celerity. Look at the 2007 interview in which someone shoots him in the leg with an air rifle mid-conversation. His unruffled reaction was a minor Internet sensation, and Herzog still tells the anecdote on talk shows, though he often forgets to mention it was an air rifle, not a real rifle, that shot him.

The marriage of Herzog with US media giants was so successful that his next film, Rescue Dawn, was an MGM star-vehicle remake of one of his own, earlier documentaries. By 2012, Herzog was recutting others’ footage, adding narration, and packaging it as his own creation with Happy People: A Year in Taiga. Critics accepted the packaging at face value. There was no secret about Happy People, which Herzog condensed from a Russian television program, but critics were content to discuss “Herzog’s motives,” with hardly a thought for the man who actually went to Siberia and shot it, Dmitry Vasyuko.

In a very real way, Grizzly Man is a line in Werner Herzog’s filmography, marking the moment he became a Hollywood filmmaker. No Herzog documentary before Grizzly Man was produced by a third party; and no Herzog film (fiction or non-) since Grizzly Man has been an independent project. Yet our mode of discussion for the man has not updated since Fitzcarraldo, thirty six years and certainly several million dollars ago.

By and large, Werner Herzog is still spoken of as the young man shooting Aguirre on a mountaintop with a stolen camera and a gun in his waistband. Still remembered as the sad-eyed mystic observing that nature is “overwhelming and collective murder.” But the late Les Blank, who filmed the infamous speech about the jungle for Burden of Dreams, was perplexed by the public’s response to the man. He told Vice: “And the first time I heard it, I thought it was purely tragic. But I soon showed the film to an audience in San Diego where I screened some works in progress, and people started laughing when they heard Herzog’s speech. It never occurred to me that what he said was funny. To me, it was very painful, and I felt sorry for the guy because he was driven to that point of view.”

Herzog seems to have drifted from the pain Blank saw in him, towards the comic irony the San Diego audience imagined. Married, stable, in LA, he has changed from an uncompromising European artist to a wealthy California-based celebrity who stops in for guest appearances in everything from Jack Reacher to Rick and Morty. He is now a talk-show circuit veteran, host of an online film school, and a regular director of branded content for multinationals.

He has become a brand. And he is content to build that brand. Perhaps he never intended this to happen, but it’s impossible to deny this is where he has arrived.

We are left with the paradox of two Werner Herzogs. Cinephiles simultaneously believe in Herzog the Philosopher who probes at hidden truths and is pathologically immune to the artifice of Hollywood, and in Herzog the Celebrity who is comfortable hamming it up in cartoons and talk shows.

Branding in the end is simply commodification; and the buying and selling of Werner Herzog extends beyond the bounds of his movies. He now runs a “Rogue Film School,” where lucky participants can attend a four day seminar including a one day meet and greet, all for a $25 non-refundable application fee and a $1500 seminar fee (with a $200 cancellation fee, god forbid), not including room or board. There, Herzog will presumably speak on how film is “not for the weak-hearted,” how it is a rarified domain only for those sturdy enough to break rules, pick locks, flaunt police, and, apparently, plunk down $1525 for a meet and greet. Those of us unable to make the cut can watch six hours of his film lessons at masterclass.com for the relatively cut rate price of $90. At MasterClass he teaches virtually alongside that other great outsider artist, Ron Howard.

By all means, there is no rule against artists, even great artists, selling out. Picasso and Orson Welles made a career out of it and their legacies remain intact. But as marketing schools teach that a brand is a promise, so we should ask what is the promise of the Herzog brand?

In 2007, Roger Ebert, to whom Encounters at the End of the World was dedicated, wrote in an open letter:

“Without ever making a movie for solely commercial reasons, without ever having a dependable source of financing, without the attention of the studios and the oligarchies that decide what may be filmed and shown, you have directed at least 55 films or television productions, and we will not count the operas. You have worked all the time, because you have depended on your imagination instead of budgets, stars or publicity campaigns. You have had the visions and made the films and trusted people to find them, and they have. It is safe to say you are as admired and venerated as any filmmaker alive–among those who have heard of you, of course. Those who do not know your work, and the work of your comrades in the independent film world, are missing experiences that might shake and inspire them.”

That is the Werner Herzog that was. An intense, comprehensive honesty, and a legacy of films driven from within, committed to truth.

That is the man the film community has never let go, even as we have another Werner Herzog: a television personality hawking self-improvement courses alongside Gordon Ramsey and Steph Curry.

To Whom Are We Beholden?

Lo and Behold represents the success of a brand carefully cultivated, marketed, and exploited. But that brand is not NetScout. Herzog’s wandering spirit, his philosophical integrity and aversion to banal civilization were repackaged and sold back to his audience. Just as LL Bean trades on its legacy as workwear for outdoorsmen to sell khakis to yuppies, Werner Herzog trades on his legacy as an Amazonian explorer to sell American Express and AT&T to an adoring film community.

Upton Sinclair once said that all art is propaganda. Likely he was correct. And so we should always be on guard, asking ourselves just what each piece of art we experience is propagandizing, and why.

Werner Herzog has spent his entire career insisting on the difference between fact and truth. “There are deeper strata of truth in cinema,” he wrote in his 1999 Minnesota Declaration, “and there is such a thing as poetic, ecstatic truth.” There also must be an ecstatic lie, in which we are led beautifully and elegantly to a dead end. Herzog also observed in that declaration: “Tourism is a sin.” And here we have Werner Herzog: Tour Guide, helping an internet security company tell us of the importance of internet security.

It is all, in the end, innocuous. NetScout has simply made an impactful film that effectively serves and works beyond its marketing origins. But will the general practice remain innocuous if another great filmmaker makes an invisible propaganda piece for say, a charter school think tank (as graced many festivals in 2009), or a toxin-spewing corporation like Monsanto (whose use of weed killer glysophate is defended by Neil DeGrasse Tyson in another industry-funded documentary), or a weapons manufacturer? What are the ethical limits of a festival like Sundance – both for creating a space for true independent cinema, and for ensuring audiences and critics know just who made their film and why?

Sundance above all has been cursed by its success. The always-elusive balance between industry access and big-money irrelevance has been especially difficult to find in Park City. A 2010 Time profile has festival founder Robert Redford worrying that “Sundance has been ‘sliding’ of late, blaming ‘ambush marketers’ for taking over storefronts to promote their swag and celebrities who just show up for the paparazzi attention.”

Was Lo and Behold essentially another example of Redford’s dreaded ambush marketing? Certainly yes. Was Werner Herzog just another celebrity showing up for paparazzi attention? Certainly not.

But it is, perhaps, because of the latter, that the film community failed to see the former. If the people who are paid to scrutinize and agonize over films missed this, what hope does any viewer have in the future to know who made the movies they’re seeing and for what purpose?